The Alabama Department of Corrections Uses a Different Dictionary

When they most likely describe today's execution in glowing terms, understand what they mean.

Barring a legal Hail Mary that’s already mostly failed, Jamie Mills will head into Alabama’s death chamber on May 30th for Alabama’s second and the nation’s fifth attempted execution in 2024. If they do, expect them to tell you some version of “without issue;” when they say that, understand their words don’t mean what they do to you and me.

Alabama’s History of Peculiar Statements about Executions

Contrasted with Alabama performing the first nitrogen gas asphyxiation this year, the state was slow to adopt the last Great White Hope of “humane” executions, only moving to lethal injection in 2002. Despite this fairly recent history, they've racked up a troubling record of what look like botched executions…unless you ask them.

Doyle Hamm

After Doyle Hamm’s death warrant expired at midnight in 2018, prison staff pulled back the curtain to reveal Hamm lying in a pool of blood, covered in track marks, and alive. Executioners had sought increasingly remote veins over the previous three hours, puncturing his bladder and mistakenly attempting to cannulate an artery in the process—all in secret, as Alabama takes the exceptional step of performing IV insertion away from witnesses. Of the bloody three-hour “execution” where no one died, then-Corrections Commissioner Jeff Dunn said, “I wouldn’t characterize what we had tonight as a problem.” Despite this confidence, the state would never again attempt to execute Hamm; he died in 2022 of the same lymphatic cancer that caused the state’s venous access issues—a complication they were warned of.

Ronald Bert Smith

This was the most macabre but hardly the only execution where Dunn’s comments didn’t make a lot of sense. Of the state’s execution of Ronald Bert Smith in 2016, Dunn said, “Early in the execution, Smith, with eyes closed, did cough but at no time during the execution was there observational evidence that he suffered.” According to media witnesses, the “early“ period to which Dunn refers lasted longer (13 minutes) than lethal injection is supposed to take in its entirety (five). These same witnesses also reported Smith moving his hands well after drugs were administered, clear evidence of consciousness—and therefore, since Alabama’s midazolam-based three-drug protocol doesn’t provide analgesia, intense pain.

“The Year of the Botched Execution“ Was Especially Hard on Alabama

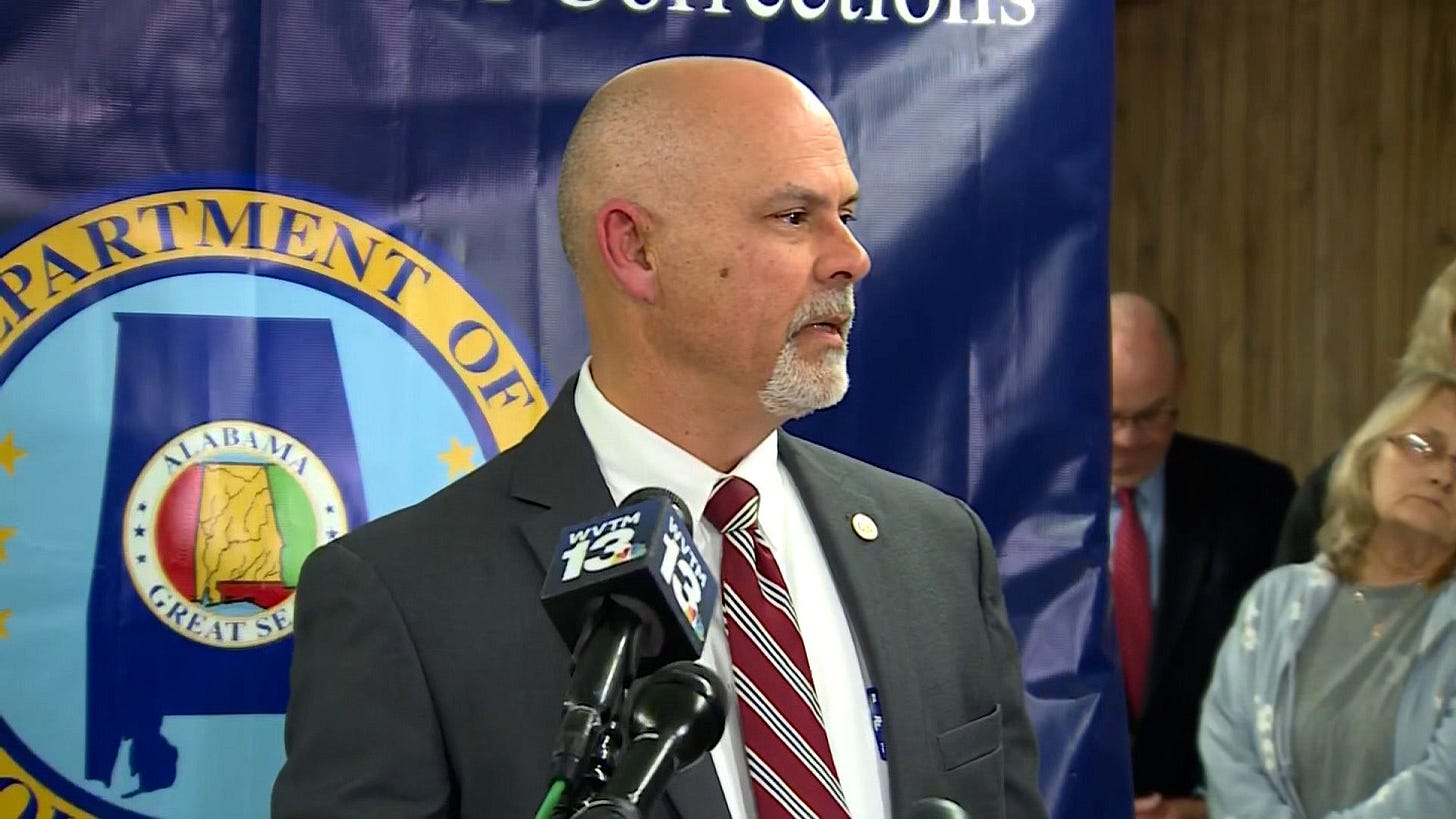

Undeterred, the state went on to botch three executions in 2022 (what activists and researchers call “The Year of the Botched Execution”), including an aborted attempt to kill Alan Miller and the three-hour execution of Joe Nathan James, Jr. A private autopsy found “unexplained cuts” in James’s left arm, suggesting staff had tried a “cutdown,” surgically peeling skin and muscle away from the vein without anesthesia (though the state’s autopsy disagreed). Current Commissioner John Hamm refused to elaborate on the delay except to say that “nothing out of the ordinary” happened.

Then there was Kenneth Smith. First marched into the death chamber in 2022 for an hour-long torture session in which technicians tried and failed increasingly invasive IV attempts before calling it off—leaving Smith strapped into the gurney, upside down, for several hours. No longer able to deny the issue, Governor Kay Ivey ordered a (never-released) review but said the problem was not the state but “legal tactics and criminals hijacking the system.”

The “Textbook“ Death of Kenneth Smith

Smith made history with his second execution date in 2024: Alabama would be the first jurisdiction in the world to try inert gas asphyxiation, pumping nitrogen into a mask to displace the breathing air with, theoretically, no other physiological effect. The state took literal pains to ensure the spotlight was flattering, depriving Smith of food or water for his final 20 hours so he wouldn’t choke on his own vomit. Despite these precautions, the Montgomery Advertiser’s Marty Roney described four minutes of “gasping for air” in what veteran death row minister Jeff Hood called “a horror show.” State Attorney General Steve Marshall, by contrast, called it “textbook,1” with Hamm dismissing Smith’s gasping as “agonal breathing.” Hamm, whose official bio lists no medical training, didn’t reveal the basis for that assessment, a pattern of deep but infrequent breathing typically found in sudden cardiac arrest.

Update: hours after this story published, local journalist Beth Shelburne revealed the state denied her public records request for Smith’s autopsy, citing an ongoing “criminal investigation.“

Alabama’s Executioners Have Every Incentive to Lie

Hamm and Dunn say these things comfortable in the knowledge that no one can really check: “the lethal-injection protocol is confidential and outside the purview of a public records request.” Though the drugs Alabama uses are known, where they come from is a state secret, and insertion of the IV catheter happens away from witnesses. The anonymous “IV team” must be “currently licensed or certified in the United States”—not a requirement until 2023—but the unredacted protocol doesn’t specify which license or certification.

This wildly different language also comes with a set of frankly existential incentives. While Alabama is prepared to use “any constitutional method“ to kill people, jury perceptions that states “humanely” kill directly correlate to death sentences; despite lethal injection’s actual record as the most botched execution method, it’s the only method that maintains broad approval. Traditional drug manufacturers won’t sell to them, requiring secret purchases from lightly regulated compounding pharmacies and a ridiculous Trump Justice Department opinion that execution drugs aren’t drugs to keep the FDA from invalidating federal and state supplies. The death penalty’s nationwide approval rating never recovered from publicity surrounding Oklahoma’s horrific execution of Clayton Lockett , which precipitated a wave of repeals and moratoriums. Letting witnesses see repeated failures to secure an IV—it’s tougher than it looks but happens without incident thousands of times per day in actual medical settings—threatens to expose lethal injection for the caricature of medicine it is and jeopardizes the ability to keep the party going.

I was born and raised in a small town in Lower Alabama. While those who know know that actually means I’m from Florida, I made more formative memories in Dothan than any Floridian city, and have a fairly native command of the local tongue—I don’t suspect something’s broken when I hear “fixin’“ or that a person headed to “Mad-rid“ or “Cay-ro2“ needs a passport and a Duolingo account. I mention all that to establish my qualifications to say this isn’t a dialectical barrier; it’s an attempt to, as we call it, piss down my back and tell me it’s raining.

Correction: an earlier version of this piece attributed the “textbook“ quote to Hamm.

I also know Cairo’s in Georgia, but if you know that, you also know it’s close enough.

Thank you for writing about this, Anthony. Alabama's Kafkaesque death machine is grotesque. We can't amplify that enough.

Horrifying. Thank you to the Instagrammer who posted the link to this piece.